At NAventures, we spend a meaningful amount of time keeping up to date on technology and fintech trends. We explore different topics to decipher fads from industry evolution, improving our foresight into the future of financial services in the process.

The evolution of Core Banking systems, the back-end systems that process daily transactions such as deposits, loans, and interest charges, is the latest topic we are trying to untangle.

These systems are, literally, at the core of every bank. So why are banks, including global behemoths such as JP Morgan, Standard Chartered, and Lloyds, selecting young, “unproven” providers over banking technology incumbents (i.e., SAP, Oracle, IBM) and their in-house solutions?

Select Banks by Core Banking Solution Provider:

At the risk of oversimplifying, we are at an inflection point in the evolution of financial services software. Mature and proven core banking solutions don’t offer the agility modern banking offerings require. On the other hand, the latest generation of core banking solutions lacks the completeness and successful track record prior generations offer.

This leaves banks facing a conundrum: accept additional risk of launching on an unfinished but future-ready solution or play it safe with a “proven” platform that may soon lack the critical capabilities required to compete effectively.

So why are banks, some of the most risk-sensitive organizations, taking on the implementation of “unproven” core banking technologies? The short answer is the potential benefits outweigh the risks.

For the long answer, we grouped the potential benefits into three categories: modularity, open ecosystems, and simplified business logic. We explain each one, how it evolved, and its implications below.

The analysis below builds upon the work of Angela Strange, General Partner at A16z. You can read her piece here.

1. Modularity

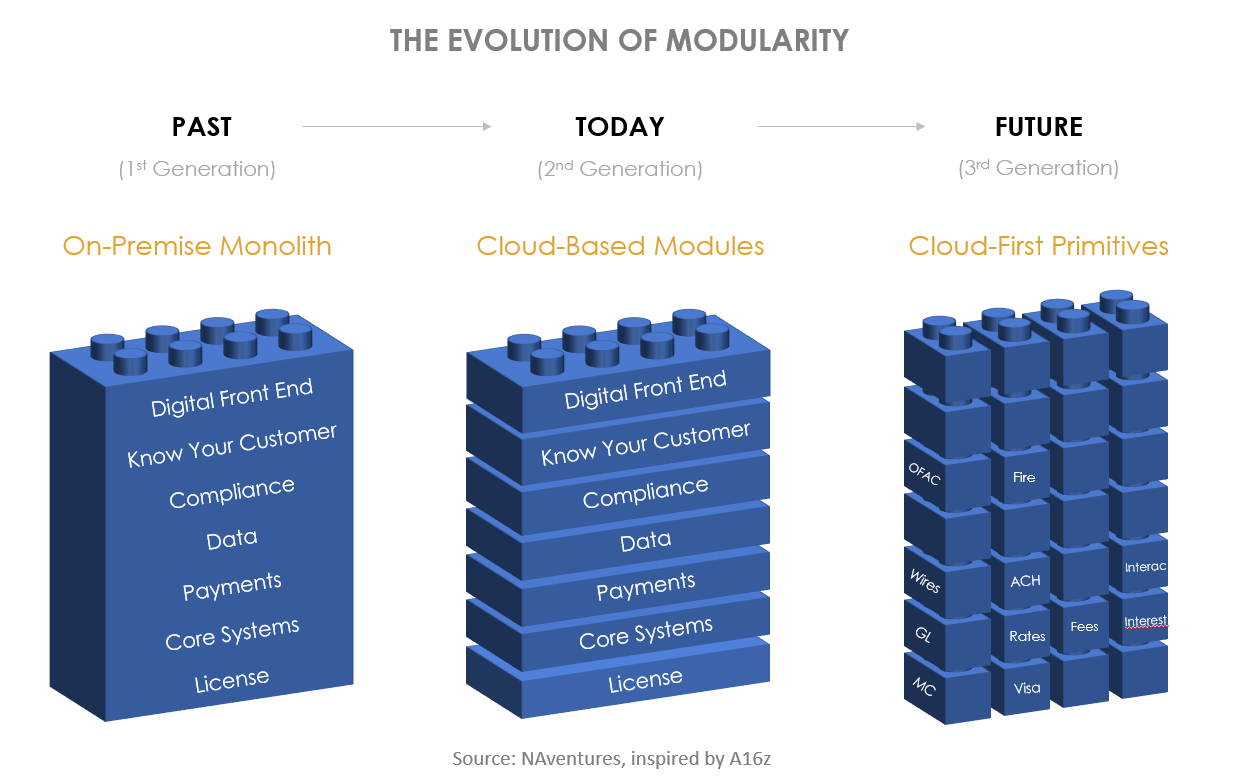

To appreciate the value of modularity, one benefits from understanding the evolution of financial services infrastructure.

First-generation banking systems were monolithic, running “on-premises” at a bank’s custom and expensive data center. These entirely customized systems were often developed over decades, incrementally adding functionality, resulting in “spaghetti code” where changes in one part of the technology could have repercussions on another. Spaghetti code has resulted in significant technology development and maintenance times and costs in banks that have failed to decouple their legacy infrastructure.

Second-generation systems consist of modular components hosted in the cloud that can be paired with other solutions in a “best of breed” approach. Under such an approach, the modules (i.e., core systems, card issuing, and compliance) best aligned to the organization’s goals are combined to form their technology stack. Modularity enables changes to be made to a module with little to no impact on the remainder of the stack. Despite delivering greater modularity, second-generation systems still lock financial institutions into large costly-to-customize or replace modules.

The third-generation systems that are currently emerging address the drawbacks of second-generation systems. By breaking down the various modules into the smallest possible components, known as primitives (i.e., interest rates, movement of funds), these primitives can be assembled in multiple ways. These primitive systems enable the development of new offerings at speed and low cost. The reduced size of the primitives also amplifies the benefits of second-generation systems.

Why is Modularity important? Imagine the different components are Legos. The smaller the pieces, the greater the configurability. With a large set of tiny pieces, you can build just about any design you can imagine. With few large pieces, you can only make what the pieces were designed to produce.

With the rise of fintech and embedded finance, banks must adapt to new and evolving products and services quickly and efficiently. Most first and second-generation core banking systems are poorly adapted to rapidly replicate or compete with non-traditional financial products and experiences.

With banking primitives, banks will have access to all the necessary building blocks to launch new products and services in weeks, not months or years. And when there is a piece missing or in need of replacement, it is easier and less expensive to replace it than get an entirely new set. The same principles apply to banking primitives.

Banks with the most modular cores will have greater agility, adaptability, and cost-efficiency than their peers – a significant competitive advantage.

Want to develop new offerings? You’ve already got all the pieces you need.

2. Open Ecosystem Benefits.

Sticking to the Lego analogy, imagine if each of these Lego-like blocks were the result of an ongoing collaboration of builders and manufacturers across the globe, continuously iterating and improving each piece.

A scientist in Siberia may develop a block that best withstands being left out in the Arctic winter. A manufacturer in Arizona may leverage this plastic formula to create a Lego that does not get damaged if left under the sun in extreme heat conditions. An environmental activist may develop a biodegradable block that aligns with her eco-friendly values. Young parents may realize that the biodegradable Lego also dissolves with saliva reducing the child-choking hazard of Lego blocks, increasing the benefits and marketability of the new blocks. The entire community benefits by sharing learnings and improving the product to meet the needs of a wider audience.

Applied to financial services, open ecosystem collaboration can improve code design and test it across a global array of fringe use cases. Rather than having to discover and solve for each fringe use case themselves, financial institutions automatically benefit from the challenges encountered and solutions developed by others.

The benefits don’t end there. Imagine if participants collaborated on and shared their new product and service designs. In addition to building on the very best blocks (i.e., banking primitives), participants could learn design improvements – even uncover completely new ways to combine the primitives to meet their customer needs. Banks could also benefit from pre-built integrations to providers designed for other participants when ready to replicate the offering.

Imagine wanting to launch a new offering and already being able to access a pre-configured pre-integrated solution developed and used by other banks or fintechs across the globe. This is the potential of an open ecosystem.

An open financial technology ecosystem may sound farfetched to some, yet the ecosystem has been growing more collaborative over time.

First-generation banking software was proprietary. Systems were built by and for banks and entirely customized. Banks maintained ownership of the software and were responsible for building, maintaining, and integrating it.

Second-generation banking software remained largely proprietary, but this time by vendors. Vendors “productized” their intellectual property as software and sold it to multiple organizations. The software company is responsible for building and maintaining the core platform, while banks are accountable for developing and maintaining their required customizations and integrations. Ecosystem benefits began to emerge as vendors started to sell “localized instances” of their software, pre-configured to meet local regulatory requirements and to contain select market-specific pre-built integrations such as payment rails. The localized instances allowed new customers to benefit from additional code often written to meet the needs of another client. Software vendors developed, owned, and controlled access to the shared code. Other integrations or customizations developed by or for a client are not available to the broader customer base.

Third-generation banking software is tackling the limitations of the last point. Open ecosystems, also occasionally referred to as Open Source, provide ecosystem participants access to the customizations and integrations developed by the entire community – not only the vendor. These integrations can be provided for free, at a fixed fee, or as a service.

Why is an Open Ecosystem beneficial? Financial technology builders can leverage the work from other engineers, product managers, and compliance experts to experiment with entirely new combinations of code, discover solutions not before possible, and leverage pre-built functionalities and integrations. As opposed to today’s model, where “code-sharing” is limited to code developed by vendors, the future is to share select code generated by other banks and fintechs.

In addition to driving innovation, this will significantly reduce the time and cost of development and maintenance. Picture a future where core infrastructure and functionality costs are shared amongst an ecosystem. An ecosystem in which members have access to a global network of pre-built integrations and services.

Want to launch a prepaid card? There’s a prebuilt plug-in for that. What to launch a fixed-fee credit card? There’s a prebuilt plug-in for that. What to launch Buy Now Pay Later Debit Cards, Crypto-Reward Bank Account, SMB Cashflow forecasting? You get the picture.

3. Simplified Business Logic

Returning to the Lego analogy one last time, imagine every time you wanted to try something new, you had to hire a team of builders, explain to them what you wanted, pay for months of building, and only see the results after a few months. You would undoubtedly build less things than if you could simply do it yourself right away.

In third-generation core banking systems, business logic sits outside of “the core.” Logic sits in a single layer where all the business logic can be programmed, updated, and edited. Combined with a simple and user-friendly UX, this layer provides a one-stop-shop for non-technical resources to immediately change the business logic that powers the entire stack, empowering the rapid execution of business decisions.

This architecture also ensures the systems’ modularity and open ecosystem benefits are maintained by abstracting the differentiated business logic from the individual modules.

In first-generation systems, such changes required that an engineering team edit business logic hard-coded and scattered across the technology stack. Such edits could often have unintended consequences impacting other functionality.

In second-generations systems, business logic is typically siloed and customized by module. This required rewriting the business logic when systems are changed. It also creates limitations where workarounds are required to create cross-silo logic, or to simply make decisions that the product was not clearly designed to do.

Third-generation systems consolidate the business logic in a single simple platform. The platform then communicates to the different micro-services. The microservices-enabled primitives and business logic platform connect like a network of services, allowing a single platform to manage business logic without requiring a separate integration layer. Often, business logic can also be defined or altered with little to no technical programming through a simple interface.

Why is Simplified Business Logic beneficial? Imagine launching new products and services in just a few clicks. A single simple, user-friendly interface enabling resources to execute business decisions rapidly is a game-changer when it comes to business agility. With abstracted and straightforward business logic, new products with customized rules and rates can be launched in minutes or days – a stark contrast to the current reality of many banks, where launching a new product can take months and cost millions.

Want to launch a new credit-card with a unique loyalty program? It can be done by a non-technical resource in a few clicks. Want to create a new savings account with promotional rates for healthcare workers? A few clicks. Want to automatically send notifications to high-risk clients to inform them that their balance is low? A few clicks.

So coming back to the main question: Why are some of the largest banks with the most complex needs turning towards the latest generation of providers for core banking software? Adding all the benefits of modularity, an open ecosystem, and simplified business logic, the competitive advantages that such systems provide are tremendous:

Increase the pace of innovation

Accelerate enterprise agility

Ease the access to external innovation

Empower non-technical resources

Reduce the burden on technical resources

The benefits are of even greater value if you believe the pace of financial services innovation will continue to accelerate and that financial offerings will increasingly compete through value-added services rather than on traditional products and price.

That being said, banks are aware of the added risk of implementing a less mature system. To access the benefits while mitigating risks, many banks choose to deploy third-generation solutions alongside their current core rather than as a replacement despite the additional costs of running overlapping systems.

By avoiding “big bang” migrations, banks can build upon and test third-generation solutions without jeopardizing their existing operations. This approach reduces the operational downside to delays in the time-to-market of innovative offerings. A worthwhile trade-off for the opportunity to build the bank of tomorrow.

Banks that become early-adopters also benefit from additional opportunities to sweeten their risk-reward calculation. Banks that opt for immature banking technology providers can benefit from discounted pricing, influence the product roadmap, and share in the company’s success through equity or warrants. Early-stage companies are often willing to make these concessions in order to benefit from market validation, anchor clients, and client references.

All this being said, unless a bank requires a new platform on which to migrate its core business immediately, investing in the infrastructure of tomorrow makes more sense than locking themselves into the constraints of yesterday’s technology.

Closing Thoughts: Third-generation systems offer the potential to remove many of the technology barriers and limitations currently stifling financial services innovation. By becoming more modular, open, and consolidating and simplifying business logic, these systems redefine the very meaning of a core.

Will the new definition of a core be the underlying ledger or the business logic layer that orchestrates and controls all the banking primitives and microservices (e.g. 11:FS Foundry)? Or will the definition evolve to encompass companies that provide the core primitives for the store of value (e.g. Thought Machine, Tuum), payments (e.g. Moov), lending, or compliance?

The core of the future is uncertain; what is clear is that it won’t be what we have today.